Search for experts, projects, publications, courses, and more.

Shunned by Brazil’s last administration, China deepened ties with state governments and the mayors of the largest cities in Brazil.

Thursday, April 13, 2023 /

By: Francisco Urdinez

Much has been said about how Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva’s third presidency will move Brazil closer to China. Brazil is China’s most important trading partner in South America, and a new agreement to conduct bilateral commerce in their respective currencies rather than the U.S. dollar is expected to further boost bilateral trade. Strengthening China-Brazil relations, especially in the areas of trade and investment, will be at the top of the agenda when Lula meets Chinese President Xi Jinping in Beijing on April 14.

As China’s economic leverage has grown, its relationships with Latin American nations no longer depend on ideological affinities as was the case during the “pink wave” of left-wing governments in the region 20 years ago. Today, China’s relationships with state governments and mayors in Latin America add additional depth and suppleness to state-to-state relations and are deeply rooted in economic interests; they are based on China’s economic importance and its position as an alternative supplier of goods that compete with those offered by the United States and Western financial institutions.

By reviewing China’s relationship with Brazil during the previous Jair Bolsonaro administration, I will exemplify that, despite the former president’s strong rejection of China, China-Brazil ties were resilient to an anti-China government and were maintained through alternative channels. This article exemplifies the adaptability and resilience that Chinese economic diplomacy has demonstrated in Brazil.

In less than two decades, China has gone from being practically irrelevant to Brazil’s economy to becoming the country’s main economic partner, both in trade and, more recently, in direct investments and finance. Brazil witnessed an unprecedented boom in trade revenues and accelerated economic growth rates in the last decade as a result of a significant increase in Chinese demand for commodities. Unsurprisingly, meat, soy and other primary product producers served as important strategic partners to China.

China was the primary trading partner of 20 of Brazil’s 27 states in 2018, the year Bolsonaro was elected president. This was unthinkable two decades ago when Argentina and the United States were Brazil’s most important trading partners. This economic boom has fostered strong ties between Brazilian and Chinese businesspeople, as well as ties between the Chinese Communist Party and Brazil’s major political groups.

During his presidential campaign, Bolsonaro accused China of “buying Brazil,” criticized the acquisition of a niobium mine by a Chinese company and turned the mineral into a campaign issue. Bolsonaro’s “China threat” rhetoric regarding investments was a campaign tactic and, in some ways, a foreshadowing of his future foreign policy. Furthermore, during his campaign, Bolsonaro visited Taiwan, which violated the “One China” principle and elicited a harsh diplomatic reaction from China. Anecdotal evidence of hostility toward China persisted after Bolsonaro was elected, even as business groups demanded a more pragmatic attitude toward Brazil’s most important economic partner.

Bolsonaro took office on January 1, 2019. He nominated openly Sinophobic diplomat Ernesto Araujo as foreign minister. Araujo claimed in 2020 that the COVID-19 pandemic was a global communist conspiracy headed by China to usher in a “new global order.”

After the World Health Organization declared COVID-19 a pandemic in March 2020, Bolsonaro’s administration took an even more critical stance toward China where the virus was first detected in Wuhan. On March 18, 2020, Bolsonaro’s son, Eduardo Bolsonaro, a member of Congress, engaged in an intense Twitter exchange in which he compared China’s handling of the coronavirus crisis to the Soviet regime’s actions in the aftermath of the 1986 Chernobyl nuclear disaster.

In an April 4, 2020, Twitter post, then Brazilian Education Minister Abraham Weintraub used a figure from a Brazilian comic book, “Turma da Mônica,” to mock China, racially insulting the Chinese and suggesting that China was benefiting geopolitically from the pandemic. These social media spats marked the de facto breakdown of any cordial relationship between the Brazilian federal government and China at the start of the pandemic.

The Chinese Embassy in Brasília gradually recognized that there was still room for cooperation if a link was established directly with state governments and the mayors of the largest cities in the country. As Brazil is a federal nation, each state makes its own laws and has some control over health care. The demand for assistance from Brazilian subnational governments coincided with the offer of assistance from Chinese businesses and labs, creating a one-of-a-kind situation in the region.

Latin America was hit hardest by the pandemic, both economically and in terms of deaths per capita. Brazil, the region’s largest country, has the world’s second-highest incidence of COVID-19 deaths.

Although Brazil desperately needed masks, COVID-19 tests, ventilators and vaccines, the national government chose not to become dependent on China. Yet, China provided the second most pandemic assistance to Brazil in Latin America, trailing only Venezuela.

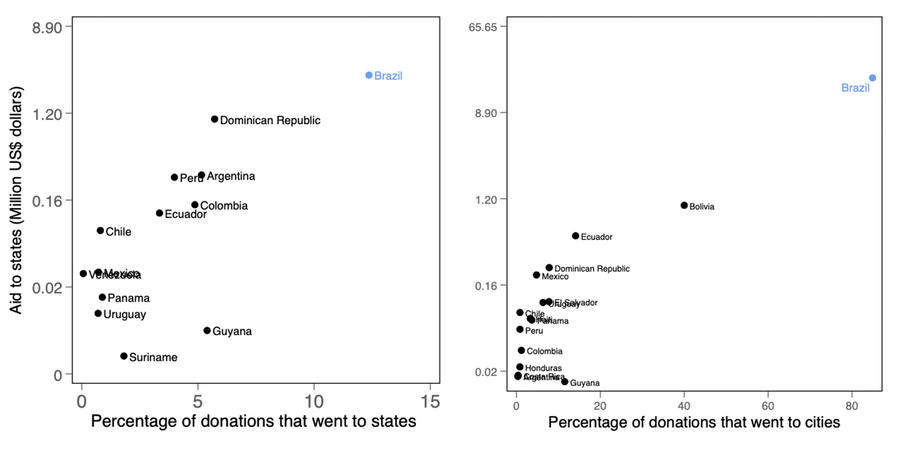

The puzzle is why, despite the existing animosity, was Brazil the second-largest recipient of assistance. Given China and Brazil’s strained bilateral relationship, subnational governments used paradiplomacy to obtain Chinese donations. Between February 1, 2020, and February 1, 2022, Brazil received 72 donations from Chinese actors (companies, provinces, municipalities, foundations and colleges) with 58 going directly to states and municipalities. According to data, Brazil was an outlier in Latin America and the Caribbean in terms of the amount of grants directed to subnational actors (Figure 1).

During the pandemic, Chinese and Brazilian actors used preexisting connections to channel product supply and demand. Chinese businesses had established positive relationships with local stakeholders, mayors, governors and civil society leaders in each of Brazil’s 27 states over the previous 15 years.

During the diplomatic crisis with China, the governors of the Federal District and São Paulo sought assistance from the Chinese ambassador to control the pandemic. Ibaneis Rocha, the Federal District governor, praised China’s attempts to contain the virus and sought its help in slowing the infection rate in Brasília, requesting donations from Chinese companies. During a press conference, São Paulo Gov. João Doria asked the Chinese ambassador for 500,000 masks. Other politicians, including Sen. Roberto Rocha and Bahia Gov. Rui Costa, wrote to the envoy requesting donations. These efforts intended to distinguish opposition politicians from Bolsonaro’s anti-China attitude.

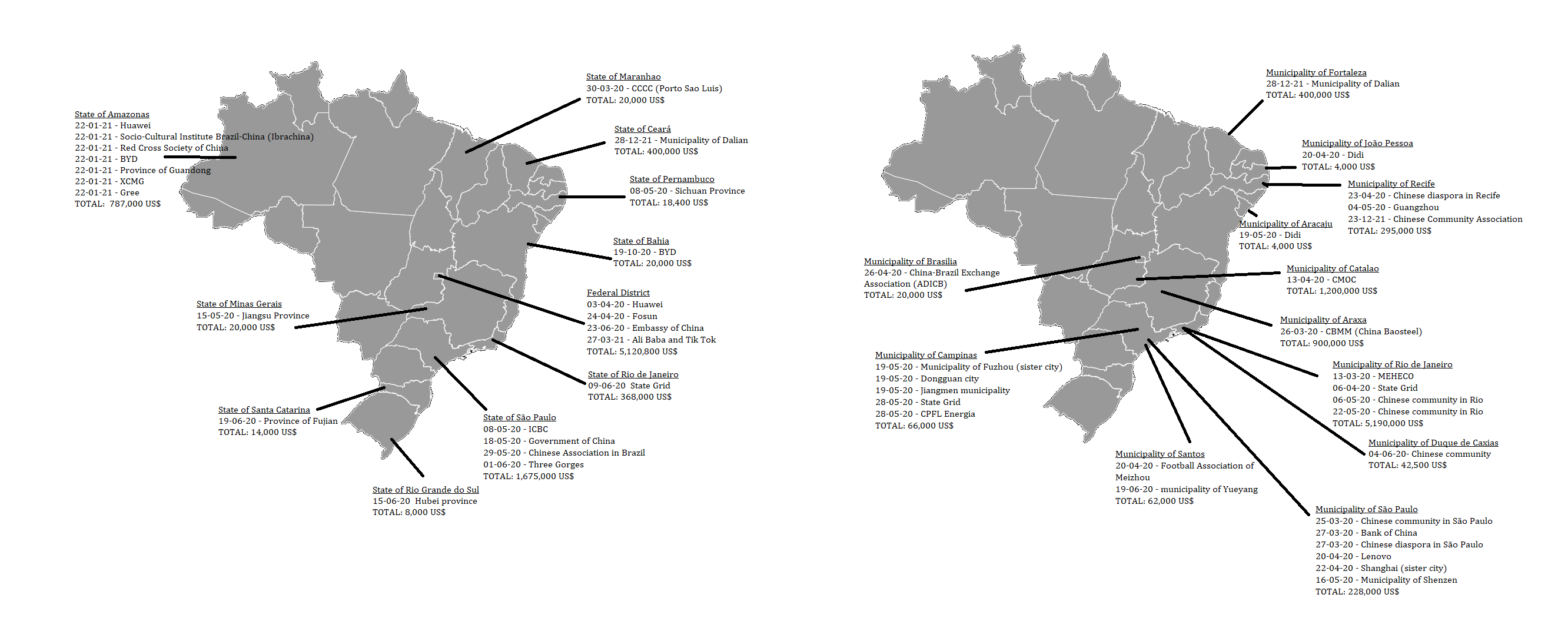

Despite tensions between the Brazilian government and China, Chinese businesses and organizations provided valuable aid. China Molybdenum Company gave $1.2 million to the city of Catalão, where it had purchased a niobium mine. Other Chinese corporations, such as Fosun, China Three Gorges Corporation, State Grid Corporation of China and Chery, gave significant donations of medical supplies and equipment to Brazilian states. Cities and provinces in China also offered donations directed to their subnational peers. The Chinese Embassy in Brazil organized an $800,000 donation of financial aid and supplies to the Amazonas government in January 2021, which included cash, masks, oxygen and food baskets from various Chinese groups. Ibrachina, a nonpartisan institute promoting Brazilian-Chinese integration, gave oxygen to Amazonas. Alibaba and TikTok gave the largest donation, providing the Federal District with 100 ventilators worth an estimated $4.5 million (Figure 2).

image to enlarge) Donations made by Chinese actors to Brazilian states (left) and to Brazilian municipalities (right)" />

image to enlarge) Donations made by Chinese actors to Brazilian states (left) and to Brazilian municipalities (right)" />

The National Front of Mayors, a caucus that gathers mayors across Brazil, grew in importance as a channel to connect municipalities with Chinese donations and solicited the Chinese Embassy’s help to buy six million doses of COVID-19 vaccines. The Chinese ambassador stated at the meeting that the embassy was committed to being a “bridge between the Brazilian municipalities and China.”

Meanwhile, the Northeast Consortium, a caucus that joins nine states of one of the poorest regions of Brazil, wrote a public statement to the Chinese Embassy to be contacted directly to channel donations of health supplies, and on a different occasion the caucus interceded when Chinese supplies to manufacture vaccines were not delivered, possibly to punish Bolsonaro.

The Northeast Consortium and the National Front of Mayors worked directly with Chinese suppliers to guarantee vaccine availability. Despite the Bolsonaro administration’s standoff with China, Brazil was forced to rely on Chinese suppliers to make COVID-19 vaccines. The Butantan Institute in São Paulo and the Oswaldo Cruz Foundation (Fiocruz) in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil’s two biggest scientific institutions for research and development in biological sciences, imported vaccine production inputs from Chinese labs, such as Sinovac, WuXi Biologic, Jiangsu Hengrui Medicine, Zhejiang Xianju Pharmaceutical and Cisen Pharmaceutical, to make more than 90% of the vaccines.

China’s influence in Brazil — and more generally in Latin America — is structural, that is, it derives from its economic weight and its ability to offer concrete solutions to a multiplicity of subnational and nonstate actors. Bilateral relations are important, but they only explain a decreasing portion of China’s success in Latin America.

U.S. policymakers can learn from the Brazil case that China’s economic leverage in Latin America no longer depends on ideological affinities. China’s relationship with Brazil remained resilient to Bolsonaro’s anti-China government. Despite the former president’s strong rejection of China, China-Brazil ties were strengthened through direct links with state governments and the mayors of the largest cities in Brazil.

U.S. policymakers should consider direct links with local governments to counter China’s influence in Latin America. Additionally, the United States should focus on economic interests to improve its relationships with Latin American nations and provide incentives to create strong business ties.

Francisco Urdinez is a 2022–2023 fellow at the Wilson Center in Washington, D.C., where he is affiliated to the Latin American Program and the Kissinger Institute on China and the United States, and an associate professor at the Political Science Institute of the Pontifical Catholic University of Chile. He is the director of the Millennium Nucleus of China’s Impacts in Latin America, which is funded by the Chilean National Research and Development Agency.

Note: The data used in this report are the result of a two-year project of examining Chinese mask and vaccine diplomacy in Latin America, whose preliminary results and data collection methodology were published in Telias and Urdinez (2021) and Urdinez (2021). In the specific case of this report, the data come from official sources (websites of government entities, social networks of politicians, press releases of Chinese donors) triangulated with press information and six in-depth interviews. Additionally, the manuscript reconstructs the peak months of the pandemic through 20 letters from Brazilian politicians to the Chinese ambassador and from the Chinese ambassador to Brazilian politicians.